Coffee Trade

In 1876-77 Major Hunter had published in India what amounted to an extensive almanac on Aden for the year 1875-76. It contains some interesting facts on the (import and) export trade in coffee. The basic import statistics are given below:

The camel-loads of coffee brought into Aden overland average out at a little over 500 loads per month, about half the number in 1879. This confirms what is written in the article Camel Loads, namely that amounts brought in overland continued to increase in spite of the freight service introduced to Aden by sea from Hodeida.

The coffee not in husk had a considerably greater value than coffee berries, and weighed a little more for the same volume. A camel could only carry so many sacks and an average load by weight works out at 3.97 cwt for coffee not in husk as opposed to 3.57 cwt for berries.

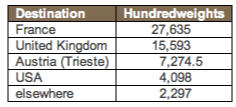

On arrival in Aden all coffee was cleaned and re-packed for export, there being a significant lesser total weight of the finished product for export. Coffee-cleaning was a thriving ‘cottage’ industry. Although the photograph of coffee-cleaning dates from around 1947 it is unlikely that the procedure had changed much since 1876! Some coffee was sold in Aden for local consumption, but most was exported. Total exports of ‘Coffee (clean)’ for 1875-76 were 56,897.5 cwt, to the following destinations: (see table below) Perhaps surprisingly, Italy imported an insignificant quantity.

Prominent coffee merchants, Bardey & Co, who operated from a three-level terraced house in Esplanade Road, Crater, would become employers to Arthur Rimbaud in 1880 and then almost twenty years later in 1899 to the iconic Antonin Besse.

By the 1880s coffee from the Mocha area of the Yemen, and the Harar area of Abyssinia which was of the same high quality, had gained a reputation throughout the world for being the best that money could buy. Not unnaturally it was more expensive than other coffee. It was in the interests of the Aden Chamber of Commerce to ensure that that this reputation was protected. The easiest way of ensuring this was to prevent inferior coffee from other areas from being sold within Aden. However Aden was a Free Port and there was no way of preventing imports; what could be done, however, was to ensure that all such imports were retained by the Port Trust in godowns before being exported. In theory this would work, but in practice it depended on the honesty and integrity of the merchants involved, not all of whom were members of the Chamber of Commerce.

Routine checks were made on Mocha coffee ready for export. On one such check in 1906 it was found that some coffee from Malabar had been mixed with Mocha. On investigation it was thought that it had come in from Massaua and imported into Aden as African coffee. There was a bigger problem in 1909 when a US Congressman stated that there was no genuine Arabian coffee being imported into the USA. All coffee from Aden was Brazilian coffee. This was soon proved to be a complete fabrication, but the investigation that was undertaken in Aden showed that no absolute guarantee could be given that Mocha coffee was unadulterated.

Mocha (and Harar) coffee was cleaned and graded before being packed in a covering called ‘garrara’ and sown with a fibre called ‘shugar’. The Chamber of Commerce were of the opinion that this formed a reliable trade-mark but their Chairman, Major Harold who was one of the Assistant Residents, pointed out that as both garrara and shugar had to be imported into Aden the Port Trust had no means of knowing whether any adulteration had occurred.

In 1913 Major Jacob was asked by the ADC to the Governor General of Bombay to send one hundredweight of the same excellent coffee that the Sultan of Lahej had offered during a recent visit to Aden. As one would expect this was best Mocha; what is of interest is that for retail purposes this was being sold by the maund, an Indian weight which varied from one State to another. In Bombay a maund was 28 lbs so the ADC was sent four maunds (sent free of carriage costs by P&O) for which he had to pay 15 Rupees per maund to the coffee merchant in Aden.

WW1 obviously put a temporary stop to the import/export trade of Mocha coffee through Aden and post-war it never really got going again. But the Chamber of Commerce had not helped itself as from 1911 some coffee from Mombassa had found its way onto the markets of Aden; by 1931 coffee from Kenya was officially allowed into Aden. This ruined the trade in Mocha as far as Aden was concerned, Hodeida being the port used from now on for the export of this commodity.

Sorting Coffee Beans

Hulling Coffee